Article continues below

If you ask Jeff Shea where he’s going or where he’s been, you better grab a drink, sit back in your favourite chair and brace yourself for a long story.

The 60-year-old California-based adventurer has walked across Papua New Guinea , Transylvania , South America’s Altiplano and the Atacama Desert. He has led expeditions into the unexplored wilds of Venezuela, and in 2007, he was part of an expedition to Greenland that discovered Stray Dog West , the world’s northernmost chunk of land. In his spare time, he’s also summited the highest peaks on all seven continents; when he climbed Everest, he eschewed the traditional, ‘easy route’ by tackling the world’s highest mountain via the (statistically) riskier North Ridge from Tibet.

Shea travels to the beat of his own drum, rarely moving directly from point A to B or following in anyone else’s tracks. Travel clubs for country collectors, like the Traveler’s Century Club , Most Traveled People and The Best Travelled , divide the world up into 325, 875 and 1,281 territories respectively. Those lists aren’t comprehensive enough for Shea, who has his own list that divides the world into 3,978 parts. (He has visited 2,330 of them and vows to complete the rest before his travelling days are over.)

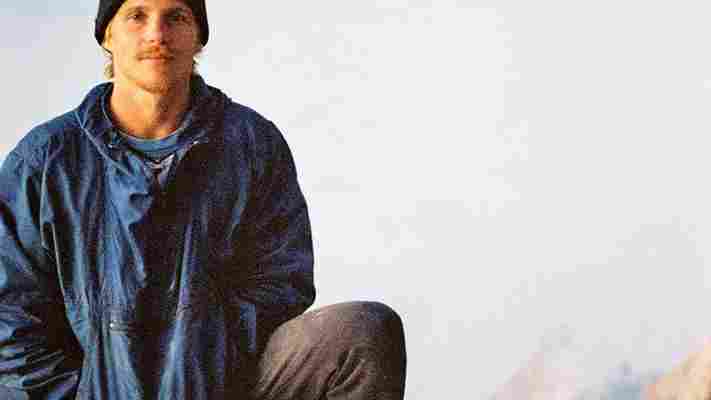

Shea travels to the beat of his own drum, rarely following anyone else’s tracks (Credit: Jeff Shea)

Shea’s passion for travel, however, isn’t about numbers, goals or risks. For him, travel is akin to a sacred experience, one that expands the mind and one’s horizons. In 2012, he founded an organisation called World Parks in order to achieve what some would consider a quixotic goal: convincing world leaders to preserve wild places as ‘world’ rather than ‘national’ parks. He is nothing if not ambitious.

“My goal is to change the world,” he said.

Q: Do you like to travel or do you need to travel ?

Travel 'is a complex satisfaction, like a life’s work'

I like to travel and I need to travel. It’s a thirst to see places, to have experiences, to expand my knowledge. It’s an education and I love to learn. You get exposed to things you can’t learn vicariously.

Travel is not a frivolous thing to me. It’s not about enjoying the sunshine somewhere. It is a complex satisfaction, like a life’s work.

Q: Where were you first exposed to the pleasures of travel?

My dad was totally against travel. But ever since I was 19, when I had a Greek girlfriend, I’ve wanted to travel to every country. She had a map highlighted with all the countries she’d been to, which motivated me.

I played hooky a lot. I went to Europe in 1975 for five months, then I moved to Louisiana, and later, I travelled with friends to South America for six months. When I came back, I finished college, finished my MBA, and, [in 1982] I met a guy who came into my dad’s fibreglass shop. He needed a tank for a fibreglass boat and mentioned that he was going to sail around the Pacific Ocean. My dad’s partner was in the room, so I waited until he left, and said, “Do you need crew?”

I got on his boat and sailed across the Pacific with him. I was gone for two years.

Q: So after spending all the time, money and effort to get an MBA, you spent the next two years away? Your dad couldn’t have been thrilled with that idea?

Definitely not! I sailed to New Guinea as crew and left the boat there. Walking across New Guinea changed my concept about what’s important. They believe that a person’s wealth is determined by how much money he’s given away rather than what he’s earned. That’s a pretty remarkable concept to me. I viewed everything through that new filter. I came from the US thinking we knew what was important and that primitive people needed to learn from us. But when you walk with these naturalists in the forest, you realize that these guys are brilliant. It imbued me with a tremendous respect. Instead of thinking that we are the advanced people, I realized we are losing a lot.

Shea was part of the Greenland expedition that discovered Stray Dog West (Credit: Jeff Shea/Reuters)

Q: You’re on the road half the year. How do you balance your life of travel with family time?

I’ve been married to an Indonesian woman for 16 years. We got married in a Muslim wedding in Indonesia and had our three children, a daughter (15) and two sons (10, 3), in San Francisco.

I’ve brought my wife to about 100 countries, so she is also a traveller. My daughter, Lani, got a Guinness World Record for being the youngest child to visit all seven continents. She was two years and three months, I believe. Someone else subsequently broke that record though, I believe. As the children grew up, we limited family travel to summer holidays so they wouldn’t miss school.

My wife is unusual; she is very easy going. She gives me a lot of space. She understands my need to travel and she knows that I really love her.

Q: Tell us about SISO, this comprehensive traveller’s list you have. Are you trying to visit each place?

I developed the SISO list to provide a permanent benchmark for extreme travellers that was not biased in any way and based on an internationally recognised standard.

SISO is designed to be permanent and unchanging. It is based on the International Organization for Standardization’s (ISO) 2003 list of subnational territories. SISO is the Shea (modified) International Standards Organization list. It is based on each country’s reporting to ISO of their subnational territories.

Because it’s broad, it provides a framework for seeing a preponderance of the world’s places. One of the things I love about these lists is that they expose you to places you haven’t thought about visiting.

And yes, I am trying to visit every one of these places. What’s more, I’m trying to photograph every one of the 3,978 provinces listed in SISO in my Worldwide Photo Project .

The salt lakes near San Pedro de Atacama, Chile, are one of Shea’s favourite places (Credit: Luca Galuzzi)

Q: Can you explain why we need world parks when we have national parks, state parks, regional parks and so on?

They are totally different. The idea of a world park is a vast area left completely untouched. You wouldn’t have a ranger or need tickets to get in, and there might be a buffer area around them.

The idea is to preserve parts of the world so that people have alternatives. The world is becoming more and more industrialized. It’s a dangerous situation because we can have an absolute loss of freedom in the human race. We’ll forget what it was like to be wild and free.

It would be the largest project mankind has ever known. This idea would change the face of humanity. It would be saying that these lands are for the people of the world and they are outside the control of government.

I’m not advocating revolution; I’m just advocating that we consider preserving land – at least one World Park on each continent.

Q: How would you describe yourself as a traveller?

I’m a traveller, a philosopher, a photographer and adventurer. It’s a not-easy-to-define ball of wax. I’m not a typical tourist. I tend to avoid sightseeing. For an expedition, I always have an objective. If it’s not an expedition, I’m pretty much just throwing myself out there, taking photographs and having experiences.

I like physical exertion. I like hardship – it’s part of freedom and happiness. You need that balance to be happy. People who only have contentment miss out on a lot. I don’t just schedule a trip somewhere because the weather is good.

Shea says that his summit of Mt Everest was the most difficult and dangerous day of his life (Credit: Jeff Shea)

Q: So what is important to you?

In 2005, I had a rare blood condition that was diagnosed as possibly fatal. There was a period of time when I was saying, ‘Holy crap, I might die.’ That’s when I started my website . I thought I better start sharing my experiences.

I took a serious look at my life – yes, I had fulfilled some dreams but I had a lot to do. Ten years earlier, my Everest experience made me question what my limits were. I set my sights on doing an expedition yearly, each more epic than the last. I wanted to test myself.

Q: You’ve certainly done that in climbing the highest peaks on the seven continents. How do they compare?

In North America, there is Denali in Alaska; Aconcagua in Argentina is the highest peak in South America. In Europe, it’s Mt Elbrus in the Caucasus; in Africa, it’s Kilimanjaro. In [mainland] Australia, it’s Mt Kosciuszko; and in Antarctica, it’s Mt Vinson. And Everest is obviously highest in Asia and the world.

In 1984, I climbed Kilimanjaro, just as a tourist with no plan to climb all seven summits. In 1993, I met a guy who wanted to climb the seven summits, and we agreed to do them together. The other six were done between 1993 and 1997. Everest is obviously the most difficult. It was the most difficult day of my life, certainly the most dangerous. Denali is probably the next most treacherous. Vinson in Antarctica isn’t as difficult but it’s hard to get to.

If the weather turns on you at any one of them, other than Kosciuszko, you’re in trouble. When I climbed Everest in ’95, it cost about $17,000. Now it costs much more. I climbed on the North Ridge from Tibet, which is more difficult. It’s a much longer day on the North Ridge. We only used oxygen on the last day, from 8,200m. You’re looking down on the whole world, it’s spectacular. But the feeling I had was, ‘How am I going to get down?’ After I climbed Everest, I vowed that I’d never climb another 8,000m peak because the risk is just too high.

The flag (designed by John Dugger) Shea holds on top of Mt Vinson marks his completion of the Seven Summits (Credit: Jeff Shea)

Q: But you’ve taken risks elsewhere. A lot of people are avoiding Venezuela, but you’ve gone on two expeditions there in recent years?

Yes. In 2010, I realized that an area of about 500,000sqkm to the south of the small river town of La Paragua in Venezuela was virtually devoid of roads and infrastructure. It seemed like a good candidate for my World Parks idea. In the middle of this vast, dense forest is the Meseta de Ichúm, the largest of Venezuela’s unique mesa-like geographic features known as tepuis . The Meseta is about 70km from north to south and about 40km from east to west. In 2013, I found out that the Meseta’s interior had never been visited by humans. I became fascinated with the idea of exploring it.

Just to get to the starting point of the expedition, we had to take a motorized canoe 250km up the Paragua River to Ichúm Falls. In 2014, we established 23 camps up the Ichúm River, searching for its source within the Meseta.

Q: What’s it like to be in this wild, unexplored place?

From La Paragua, you’re out in the middle of nowhere and you’re going to a place that’s even more in the middle of nowhere. The scenery is spectacular. The tepuis are gorgeous, particularly because we were seeing them from the river.

Shea is fascinated by the mesa-like tepuis of Venezuela (Credit: Paolo Costa Baldi)

I led the expedition of three men from Caracas and five Shiriana Indians living near the Meseta on the Paragua River.

Traveling up the Ichúm River was fantastic but gruelling. To travel upriver through dense rainforest, we designed lightweight boats made from PVC tubes, inner tubes and plastic netting. From day one, we had to shuttle our gear and boats over the massive Ichúm Falls, then go upriver through rapid after rapid for weeks. When the river rocks became impassable or we reached a waterfall, we had to disassemble the boats and carry them through the forest, hacking our way with machetes.

One night, when we were doing the final shuttle of gear for the day, the propeller on our motor broke. We stood waist-deep in water on rocks in the middle of the river. We noted several crocodiles around us, their eyes shining orange in the light of our headlamps.

The Shiriana Indians confirmed to us that no one else has visited this area. Once in the Meseta proper, there was no sign of life at all. We could have encountered people that had never been seen before. The Shiriana were afraid of encountering Guaíca, wild savages. They also believed there was an evil spirit high up in the Meseta. They were terrified. So, at Camp 15, four of the five abandoned us.

Q: What did you accomplish?

We discovered Bactrophora Dominans, a really odd-looking grasshopper, at Camp 22. Only a few specimens of it have been found in all of history. This was the first one sighted in Venezuela. I co-authored a paper on it that was later published in the scientific journal, Checklist. We established a new dispersion area for this insect.

We also were the first humans to get to the centre of the Meseta. I want to return for a third and final expedition to find the source of the Ichúm River.

Shea’s walk across the Transylvanian fields was one of his favourite trips (Credit: Bereczki Barna/Alamy)

Q: What are some of the other wild places around the world that are important to you?

South from San Pedro de Atacama, Chile, there is a place called Socaire. If you go even further south, there is a salar , an ancient salt lake high in the Andes, that is spectacular. The Altiplano lakes have this deep blue water. They’re surrounded by hills with golden tufts of grass and grazing vicuña with nothing around for miles.

But I also like to go to places that aren’t noteworthy at all. For example, I walked across Transylvania. I was driving across it and decided to walk instead. I took a daypack with a really light sleeping bag and camera and that was it. I walked through fields and streams and farms; it was one of the best trips I’ve had. It’s important to create your own adventure and develop your own ideas.

You can get an unfiltered view of the world through travel"

Q: What do you believe people can accomplish through travel?

It changes things for the better. First-hand learning is unadulterated and pure; it’s not tainted with other people’s impressions. You can get an unfiltered view of the world through travel.

I’ve discovered that there are no limitations. I can go anywhere. That’s how I’d like to inspire people. You can go anywhere on the planet under your own power.

Join over three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook , or follow us on Twitter and Instagram .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.